What would it mean to ‘queer’ creative health? Why might we need to, and, if so, how? I was given the opportunity to first delve into these questions through a PhD scholarship I completed in 2019. My literature review explored longer histories of the field of Arts in Health as part of exploring its relationship to people and place.

In a book I recently developed from my thesis - titled When Was Arts in Health? A history of the Present - I further chart social movements for health, including those that arose within LGBTQ+ communities. I aim to show how particular art activisms, performed in the 1980s, were part of the emergent field of Arts in Health that developed in the 1990s. In fact, they helped define the field into a distinctive ‘movement’ with narratives and aims of its own.

A 1999 collection of essays, The Arts in Health Care, for example, held-up the AIDS Memorial Quilt as exemplar of the ‘healing arts’, a community-based format that could soothe and heal collective pain as well as agitate for social change. One gay activist quoted, makes no distinction between these two aims. Speaking at the height of the AIDS epidemic, Douglas Crimp says how:

The violence of silence and omission almost as impossible to endure as the violence of unleashed hatred and outright murder. Because this violence also desecrates the memories of our dead, we rise in anger to vindicate them. For many of us, mourning becomes militancy

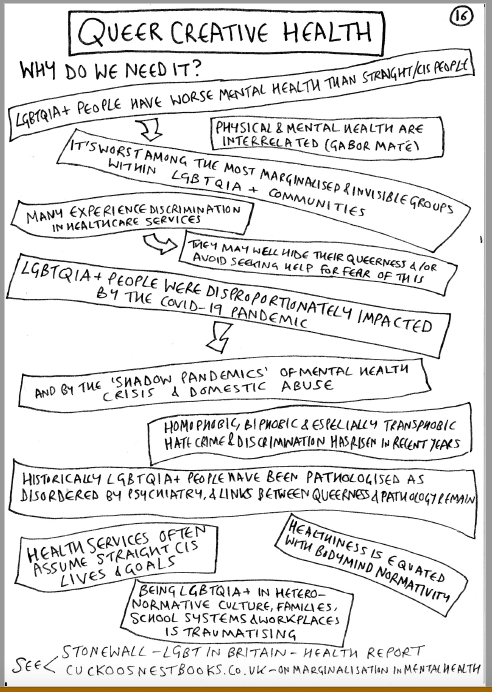

We see Crimp’s wounded, trenchant sentiment echoed in recent events such as vigils organised in response to the murdered (trans) teenager, Brianna Ghey. Differences of opinion emerged within the LGBTQ+ community about to what extent these spontaneous gatherings of remembrance should, or should not, be seen as forms of political protest. Similar sources of oppression are identified as deadly threats to our health, then as now: namely anti-LGBTQ+ media outlets and government actors working hand-in-hand to create hostile atmospheres that feed all too directly to rising hate crime figures.

Since gaining my doctorate, I have criss-crossed between the lines of research and practice, reflection and action, ‘healing’ and ‘agitation’. Last year, I became Education and Participation Manager at a new arts venue called QUEERCIRCLE. This was set-up by Ashley Joiner in 2016 as a forum for LGBTQ+ arts and artists to support dialogue and exchange. He signed a lease on a new building in the Design District in 2022, promising a space where ‘culture and the arts’ could ‘intersect’ with ‘social action’.

By the time I arrived, funds were already in place for QUEERCIRCLE to fashion a health and well-being programme from scratch, an exciting, if also slightly daunting opportunity. Building on existing contacts, I threw out calls for potential partners through networks and groups such Opening Doors and Flourishing Lives. London Arts and Health also provided a support forum to explore the interface between creative health and queer lived experience, allowing me to speak to colleagues across London as part of the ‘Actioning Creative Health’ group.

The main offer at QUEERCIRCLE, we soon discovered, was social space itself. The impetus for the creation of QUEERCIRCLE was the acceleration of the loss of LGBTQ social venues and spaces during the pandemic. University College London researchers led on the recorded loss of this social infrastructure (Campkin and Marshall, 2018) and we recruited researchers from UCL’s Engagement Team to evaluate our pilot programmes.

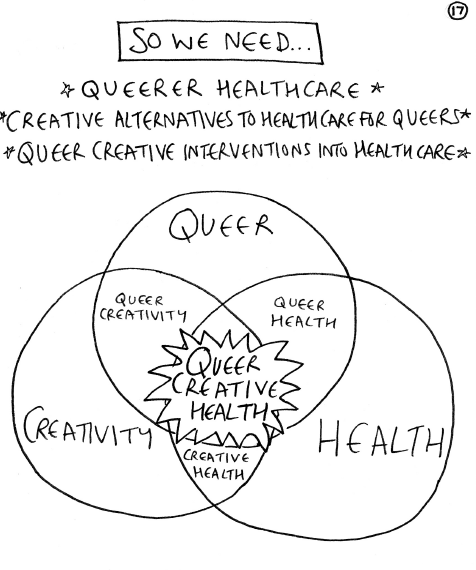

As most reading this blog here will know, the new title for the field of practice known as Arts in Health is Creative Health – named after the APPG report of 2017 which adopted this title. Since then, many new institutions and organisations have taken-up reports’ recommendations. But there is no specific reference to LGBTQ+ communities in this report. Rather, a broad paragraph cites the ‘deleterious effects of social marginalisation’ amongst many different groupings, including those that arise out of ‘gender and sexuality identity’.

And so, over six months, we piloted creative health programme across many LGBTQ+ contexts. We tested targeted workshops across all ages, working with families with young children, youth groups, sixth form students, as well as older residents of Tonic Housing - a residential community for older LGBTQ+ people. Artist Kit Green led on debates around varied ‘transitions’ through all our life stages.

Other workshops explored stigma more directly. Researcher Gemma Lucas used movement and yoga as a way of understanding how we embody and can address unwelcome feelings of shame. While zines became the media through which feelings of collective grief could be expressed for workshops facilitated by June Bellabono. Creative writing, crafting, printing and life drawing were thrown into a mix of workshops devised by and for POC, trans and lesbian groupings, as well as workshops/public events open for all.

A final get together for participants, artists and researchers took place last January allowed us to share thoughts on what it was we thought we were all doing. Many rich discussions ensued around how the normative models of research and practice didn’t fit in so well with LGBTQ+ experience. Researcher Yasmin Jjiang has since written up evaluation findings as part of a report titled Queering Creative Health due to made public on May 19th.

MJ Barker has also provided a complimentary zine, a way to break down hierarchies between academic and community knowledge. We hope these two joint report-zines can provoke a bigger conversation about the intersection between creativity, queerness and health - and what this means as we seek to address recent as well as longstanding adverse (mental) health impacts resulting from stigma and discrimination.

Through adopting ‘queer methods’ the divide between ‘what we wanted to find out and how we found out about them’ could better bridge gaps between researcher and the ‘researched’. The report cautions against talking about ‘community’ too generally, noting the importance of social or political context, as well as naming some of the particularities of lived experience of marginalisation. If this all sounds like something you’d be interested in further exploring with us, get in touch as we expand our Queering Creative Health network.

Frances Williams is Education and Participation Manager at QUEERCIRCLE.org and the report will be released on 19 May 2023. She can be contacted at [email protected]. Her book When Was Arts in Health? was published by Palgrave McMillan in March 2022.

Frances Williams is Education and Participation Manager at QUEERCIRCLE.org and the report will be released on May 19th. She can be contacted at [email protected]. Her book When Was Arts in Health? was published by Palgrave McMillan in March 2022.