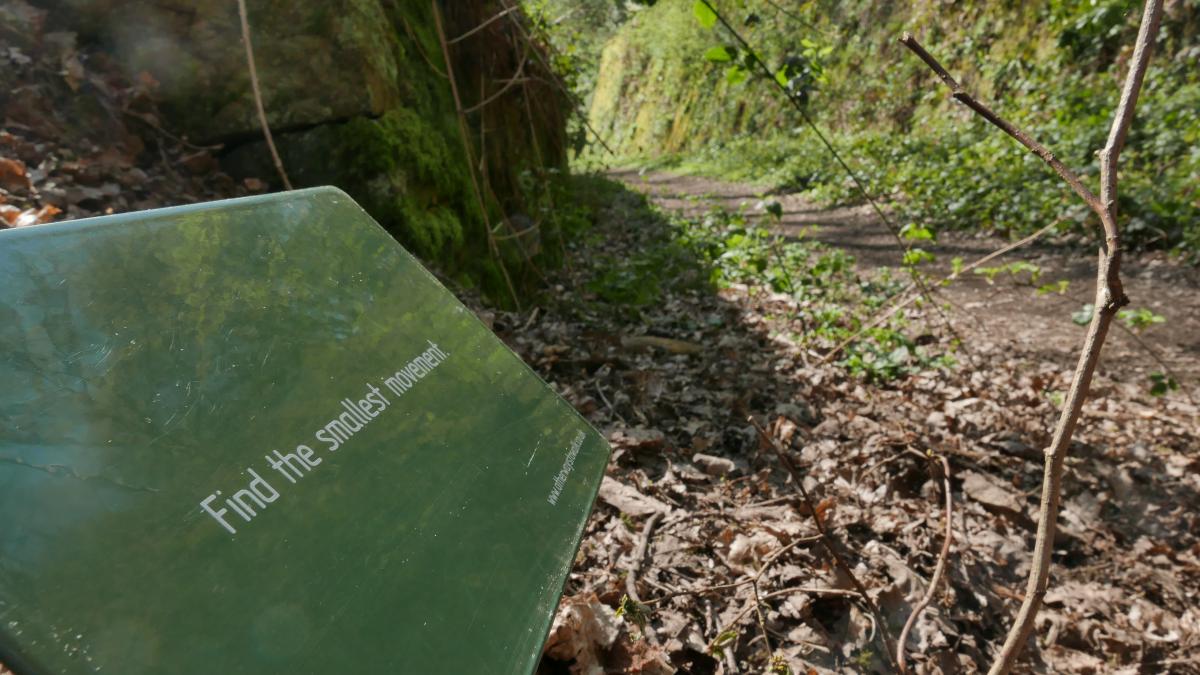

Guest blog by Rachel Howfield Massey, Other Ways to Walk

Rachel is an artist, mindfulness instructor and forest guide. She is also Arts and Health Coordinator for Arts Derbyshire and CHWA Regional Champion for East Midlands.

There are moments of great beauty available to us every day if we are willing and able to experience them. Perhaps we squint at the world through the prism of a raindrop on a window and enjoy the intangible and ephemeral qualities of light, colour, flickers of movement and shadow – or it remains invisible to us as we are swept along in a torrent of thoughts, wishes, hopes and fears. In a time of great uncertainty, we can choose how we want to experience the world, moment to moment – and welcoming in nature can have measurable benefits.

There is a global pandemic, people are experiencing isolation, fear and uncertainty – and as many of us working in arts and health could have predicted, the main sources of sustenance and comfort are culture and nature. Those with endless lonely hours ahead of them each day find community in virtual choirs, distance dancing on the street, waving at a neighbour while admiring the sunset from an open window. Essential workers caring and cleaning for the sick and elderly find solace and hope in appreciating the spring blossom, escapism in TV, radio or a book. Poetry is resurgent.

If culture and nature are proving to be fundamental to wellbeing, then there is no more important time for celebrating and sharing the benefits of nature connectedness. Studies show that frequent connection with nature can lead to clinically significant health improvements; reduced levels of cortisol (indicator of stress), improved immune response and improved sleep.

Despite reliable indicators that our relationship with nature is breaking down as our urban lives become faster paced, lockdown and isolation have provoked a craving for greenspace. This fundamental desire for the nourishment of fresh air and natural landscapes can be traced back through history; indeed it fueled the Kinder Mass Trespass in 1932, eventually leading to public access to private land. Once again we face inequalities of access to greenspace as the government are imploring people not to linger in parks or visit countryside beauty spots and coastlines, with far more serious consequences for those who don’t own land in the form of a garden.

Current research[1] shows that feeling a sense of connection to nature is more important for wellbeing than contact with nature; simply getting out into nature is good for health, but does not improve our sense of worth, purpose and meaning in the way that connection to nature does. Nature connection develops slowly, through personal experience, cultivating curiosity and taking time to notice the details. We feel connected to things when we become familiar, interested and emotionally attached. It is something to be experienced, not learned about.

At its simplest, nature connection needs a willingness to commit a few minutes of time to notice the details in the natural world in everyday life – be that in a weed in a crack in the pavement, a new shoot on a pot plant, or a view from the window. There are even measurable benefits from connecting with nature in a photograph or on a screen. Health inequalities due to social determinants have all too often been neglected by policy makers and now inevitably the most vulnerable are the worst hit by social isolation and its consequences. No-one is claiming that connection to nature can compensate for this serious, structural inequality, but it may help ameliorate some symptoms of anxiety, loneliness and stress. Whilst long meandering walks can offer abundant opportunities to connect with nature, it can happen just as effectively in a few moments waiting for the bus or watching clouds through the window.

It is possible for this open-ended discovery to lead people into a deeper connection as they shift from a busy mental state of ‘doing’ into a more contemplative state of ‘being’ which is so beneficial in opening us up to connection with nature – especially when circumstances have forced many people into ‘doing nothing’. There are techniques to support people to become receptive and relaxed in nature; in my practice it’s fundamentally about facilitating ways of seeing through creative activities, mindfulness, fieldcraft and guided looking. The Five Pathways to Nature Connection[2] involve using the senses, appreciating beauty, tuning into emotional responses, finding meaning and cultivating compassion.

It’s easy to believe that artists and creatives are probably better placed than most to create new and meaningful ways for people to connect with nature. Tristan Gooley, an expert in navigation using signs in nature said that the only other people he ever met who noticed details in the landscape in the same way were artists. Artists have a special power to show us something about ourselves that we know but can not articulate clearly – skillful use of metaphor, form, pace, texture can help express something subtle, barely understood in a way that stirs the soul. Nature connection is about moving from looking to really seeing, from hearing to deep listening – and these are creative acts.

Creative people are comfortable with navigating the unknown in search of new possibilities, they bring a curious mind, an understanding of how to make something out of nothing and few professions demand such a high tolerance of uncertainty alongside devoted commitment and fascination for their work. It can be difficult to attach an economic value to this ‘artist mindset’ but it is certainly coming to the fore now with so many offerings from the cultural sector to help people survive isolation. We can only hope that this will help advocate for the true worth of creatives when we start putting the world back together.

For now, as we try to endure uncertainty with good grace, it’s reassuring to remember that the end of the journey is not always as satisfying as we might expect - and there’s always benefit in taking time to savour any bright moments along the way. So next time you notice a fresh new bud or beautiful bird song, take a few moments to fully experience it – it’s scientifically proven to do you good.

Rachel Howfield Massey

Other Ways to Walk

[1] Finding Nature Blog, Professor Miles Richardson, Nature Connectedness Research Group, University of Derby: https://findingnature.org.uk

[2] Five Pathways to Nature Connection https://findingnature.org.uk/2018/12/06/applying-the-pathways-to-nature-connectedness/